Northumberland has an amazing variety of rocks and fossils, equal to any around the UK, that underpin wildlife and habitats and now, we'd like to invite you to vote for Northumberland's favourite rock and favourite fossil. The vote will be open for 30 days until the end of August.

Literally the bedrock of the world’s heritage, economy and tourism, rocks have lots to tell scientists about things that are happening to landscapes as the world’s climate continues to change.

Following on from Northumberland Wildlife Trust’s 50th Anniversary Rock Festival and subsequent best-selling book aptly titled Northumberland Rocks, the wildlife charity, together with its partners: The Natural History Society of Northumbria, Visit Northumberland, Northumberland & Newcastle Society and North Eastern Geological Society, has decided to keep the enthusiasm for geology going by launching the first online public vote to find the county rock and fossil for Northumberland.

For the whole of August, voters will have a shortlist of five great rocks and fossils to choose from.

Rock shortlist

1. Dolerite

Of the Whin Sill, the foundation of much of Hadrian’s Wall and castles on the coast

More info

The Whin Sill is made of a rock called dolerite. It was once molten magma, like granite, but because it occurs in a much thinner layer nearer the surface it cooled faster and so the mineral crystals in it are much smaller and you can hardly see them with the naked eye. The Whin Sill is a dark grey, hard rock. It usually has vertical joints and fractures (caused by its cooling). You can recognize it in the landscape because its hardness means it often creates a prominent cliff (scarp); like the one that the more dramatic bits of Hadrian’s Wall is built on and and along the coast at Bamburgh and Dunstanburgh.

When molten the rock was at a temperature of around 1200ºC. At that time, 295 million years ago, northern England was being stretched during an episode of mountain building caused by movement of the tectonic plates. The molten magma was injected into weaker places in existing sedimentary rocks (rocks like limestone and sandstone) as “sheets” up to about 50 metres thick. These sheets were then tilted south and eastwards by around 10 degrees by earthquakes, giving the very characteristic “scarp and dip” or “cuesta” landscape you see along Hadrian’s Wall country. You can see it best when driving along the B6318 Military Road.

Dolerite also produces a very characteristic vegetation – called Whin Sill grassland. Many plants struggle on these thin soils. It is nutrient-rich, but releases nutrients slowly, and on its shallow soils in dry seasons the vegetation can be physically-stressed. These shallow soils and bare rock support a distinctive set of species. They include chives, and annuals such as annual knawel and long-stalked crane’s-bill. A particularly attractive herb is maiden pink.

Because of its hardness the dolerite of the Whin Sill has and is used extensively for roadstone – the rock fragments that are mixed with asphalt in “tarmac”. More than 100 years ago it was also quarried and shaped into “sets” to make cobbled streets.

2. Granite

Of the Cheviots - an ultra-hard, mineral-packed rock that forms the mountains of the Cheviots

More info

Granite is a very hard rock that was once molten magma deep underground and then slowly cooled and crystalised. So it is a rock with lots of quite big minerals (quartz, feldspar and mica) all intermeshed. The minerals are most commonly white and black but can often include pink ones too. It is very hard and usually resists erosion and forms hills and mountains.

We only have one granite that reaches the surface in Northumberland and that is the Cheviot granite that forms the mountains of the Cheviot range and was later exposed by erosion of the overlying rocks. But there is another granite that is found deep underground in the very south of the county and called the Northern Pennine or Weardale granite. However, you may occasionally find boulders and pebbles of granite from south west Scotland; they have been carried here by ice sheets during the last Ice Age. Because they are hard granites usually form high ground. They are also impermeable so they are usually ill-drained and boggy with poor soils. Sometimes the weathered top of the granite sticks out of the landscape forming tors – like those at Great Standrop near Cheviot.

Granite has lots of silica, and not many minerals yielding plant foods, so it produces infertile, acidic soils, typically with heather and coarse grasses like moor mat grass. However, with heavy rainfall on the high ground much of our granite is covered by waterlogged soils with a blanket of peat, as Pennine Way walkers on the Cheviot know only too well.

Although the Cheviot granite is not quarried, other granites like the one at Shap in Cumbria, are used a lot, largely because they are hard and colourful. You will see granite used as roadstone, as kerb-stones, monuments in churches, shop and building facias, including Metro stations, and of course our kitchen worksurfaces!

3. Coal

Part of our heritage and vital for industry in the 19th and 20th centuries

More info

You can still find coal in its original layers in the low cliffs along the Northumberland coast or in the valleys and denes such as Haltwhistle and Blaydon burns. Usually you find it as thin seams, above a softish light grey rock (the fossil soil, or seatearth). Coal is a relatively soft, black, often shiny sedimentary rock, that breaks up quite easily into rough cubes.

Coal was once plant matter that decayed only slowly under waterlogged conditions and after being buried deep under other rocks for millions of years became compressed into the black rock we see today. Most coal in Britain comes from the Carboniferous period when, for many millions of years, the environment was sub-tropical swamps and forests. It is a fossil fuel, a form of carbon that usually has several other elements, like sulphur, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen. Coal is used to produce energy for heating homes and providing power, it is also used as a fuel to produce iron and steel. Burning coal in power stations is the biggest single contributor to C02 emissions and we are trying to dramatically reduce our use of coal so that we cut down the amount of carbon in the atmosphere and stop our planet over-heating.

Because coal is a relatively soft rock in nature it usually doesn’t produce a distinctive landscape. However, because of all the deep mining and opencast coal mining here in north east England, there is a “coal landscape”made by us humans. Not so many years ago that used to be big spoil heaps of colliery waste, but most of these have now been restored (like Northumberlandia). Other signs of coal in our landscape are ponds and depressions where the ground has subsided over old coal mines and also deliberately flooded areas during restoration of past opencast sites (like Hauxley). Some plants like coal landscapes, like, for example the greater spearwort on subsidence wetlands and formerly a medley of opportunist plants on pit heaps.

4. Sandstone

Used in building the majority of our towns and monuments, including Grey Street in Newcastle, Hadrian’s Wall and Alnwick Castle

More info

Sandstone is a rock composed of sand-sized grains. Those grains are mostly quartz but there are often rock fragments and pieces of shells too. It looks like sand cemented together and if you look through a hand-lens you can see the sand grains. It’s most common colour is pale brown but you will see grey, red and purple sandstones too. Looking at sandstone from a distance the most noticeable thing are the regular layers of the grains – called bedding. Sandstone is the most common rock you will see in Northumberland. You can find it almost everywhere. Simonside is a great place to see it – the rock there is called the Fell Sandstone - and on the coast, for example at Tynemouth Castle. You can also see it used as building stone everywhere, from Hadrian’s Wall to Grey Street in Newcastle.

Most sandstone in Northumberland was formed from sand carried down ancient rivers and deposited in and on deltas and beaches over 300 million years ago in Carboniferous times. But at Tynemouth there are younger sandstones formed in a hot desert. Many sandstones are hard and stand proud in the landscape, forming ridges and escarpments, like those around Rothbury, or cliffs like those at Newbiggin. Sandstone usually produces a well-drained, acid habitat, one that is liked by plants like heathers and heaths.

Without sandstone our county would look very different! The majority of our buildings and walls are made of sandstone. It’s a rock that splits easily into rectangular blocks and can be easily dressed and carved. Take a look at Hadrian’s Wall, Grey’s Monument or Alnwick Castle. Old sandstone quarries are everywhere, from Haltwhistle to Berwick-upon-Tweed and from Kielder to Kenton.

5. Limestone

Full of fossils, it forms unusual landscapes, from pavements to caves and potholes, and creates botanical hotspots for unusual plants

More info

Limestone is a rock mostly composed of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal varieties of calcium carbonate. Like a lot of rocks it comes in various shades of grey, but it often has fossils in it (you can usually see them better with a magnifying glass). When you look at a cliff of limestone it has wavy horizontal lines and cracks separating the layers of rock (unlike sandstone which has straight lines and Whin Sill which has vertical cracks). Because limestone is soluble it also dissolves in weak acid made by rainwater percolating through soil. Layers of limestone occur across Northumberland in a big arc from northeast to southwest. One of the most prominent limestones is called the Great Limestone and you can see it in many quarries and along many parts of the coast.

Limestone forms by the minerals precipitating out of sea water, mostly through biological processes – many billions of microscopic animals, but also sea creatures like shells too. Our Northumberland limestones were deposited about 320 million years ago in the Carboniferous Period when our environment was a warm shallow sub-tropical sea!

Because it dissolves limestone often produces special landscapes, with potholes (sink or swallow holes), caves and “pavements”; there is usually no water at the surface because it has percolated down through cracks and fissures. Limestone landscapes all over the world have a name – “karst”.

Many of the world’s botanical hotspots are on limestone. In Northumberland many less common species are found on limestone, or on thin soils formed above the rock. Among these are hairy rock-cress, hoary plantain, small scabious and autumn gentian. Limestone pavement is a very special habitat for plants, but we only have a tiny bit, beside Broomlee Lough.

We couldn’t live without limestone! As well as being used as a building stone it is used for making cement and mortar and for producing steel. One third of global oil reservoirs are found in limestone. We use it for treating acid soils, and for many industrial chemical processes. Did you know that it is part of toothpaste and paint and it’s even added to flour and bread!

Fossil shortlist

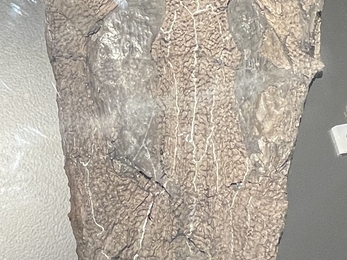

1. Lepidodendron and stigmaria

The 300 million year old fossils of tree trunks and roots

More info

These fossils are parts of the same tree: Lepidodendron is the above ground “trunk” and Stigmaria is the buried “root”. Early palaeontologists weren’t sure about that they were the same plant so give the fossils they found different names! Lepidodendron has scaly, diamond-shaped patterns and Stigmaria lots of holes in rows. They were once plants (club mosses) that grew up to 50 metres high in Carboniferous coal swamps. They are a genus of tree-sized lycopsid plants that became extinct here when the coal swamps disappeared and deserts arrived around 300 million years ago.

You can find both of these fossils in sandstones and shales all across Northumberland, but the best places to look are on rocky foreshores along the coast, places like Howick and Cocklaw beach. You might find them as just imprints and patterns on the rock, or be lucky enough to pick up a piece.

2. Anthracosaurus

Also know as the Coal Lizard - a vicious predator long before the dinosaurs that hunted in coal swamps and on display today in the Great North Museum: Hancock

More info

They were fearsome predators long before the dinosaurs were around. Anthracosaurs are a group of animals that lived in coal swamps around 320 million years ago. Palaeontologists have found several different types and given them some great names. There’s Eogyrinus – the Dawn Tadpole. Pholiderpeton - scaly creeping animal. Or how about Megalocephalus – Big Head! Back then in the Carboniferous period they hunted fish and other amphibians in warm, sub-tropical coal swamps and their long body shape helped them swim and catch prey between the roots and vegetation underwater.

Anthracosaurs were found in a shale in a coal mine at Newsham, near Blyth in the 19th century. Lots of animal and plant fossils were found by coal miners there. They gave them to a local man Thomas Atthey who was a grocer in Cramlington and an amateur palaeontologist. He studied them and gave most of them to the Great North (Hancock) Museum. The Megalocephalus’ fossilized skull and bones and a reconstruction of an Anthracosaurus are on prominent display there. The fossils found in Blyth are rare and only a handful of very large amphibian fossils from this period of Earth’s history exist anywhere in the world. Because it is so rare it is very important.

None of these animals are alive today but their evolutionary descendants are other amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. They are an important link in the evolution from fishes to land animals.

3. Corals

Animals that live in the sea, usually when it’s shallow, rocky, clear and clean

More info

Sometimes they live in colonies and sometimes as individuals. They have been around for a long time. They make a skeleton out of calcium carbonate and live in it with their tentacles sticking out so they can feed. The fossils of corals we find in Northumberland are from the Carboniferous period, so around 330 million years old. But corals go back much further to the Cambrian period 500 million years ago.

They live with their base attached to a rocky sea bottom. We can use their fossils as proof that the area where they are now found was once under the sea and that the sea was shallow. We usually find them fossilized in limestone. Good places to look for fossil corals are rocky foreshores along the coast, or in old quarries where there are broken rocks lying around. These animals are still around today and like in the past they form reefs – especially in warm seas close to the tropics. Can you believe that Northumberland was once under a warm coral sea!?

4. Crinoids

An ancient ‘lily of the sea’ and often referred to as St Cuthbert’s Beads

More info

Crinoids are an animal that lived in the sea. They are one of the echinoderms and you usually see parts of their broken stems as cylindrical “beads” called ossicles fossilized in the rocks. They are perhaps the one of the most common fossils you will find on the rocky limestone foreshores of Northumberland, but also in quarries and in river shingle inland. They are sometimes called sea lilies. The fossils of crinoids we find in Northumberland are from the Carboniferous period, so around 325 million years old. But crinoids go back much further – 500 million years ago in fact to the Cambrian period. Crinoids lived in fairly shallow seas and their stalk/stem was attached to a rocky sea bottom. They are used by geologists as an indicator of marine conditions.

They are usually found fossilized in limestone. Good places to look are rocky foreshores along the coast. 600 different types of the relatives of crinoids are still alive today.

5. Brachiopod

Sea shells that lived in the warm tropical seas that covered Northumberland 320 million years ago

More info

These sea creatures had two hard shells. They look like many sea shells (e.g. cockles and mussels) but they are not; they are a separate group of animals completely - brachiopods. One type, Gigantoproductus, grew up to 15cm across. Gigantoproductus lived about 330 million years ago in the Carboniferous period, but its brachiopod ancestors go back much further than that, maybe 600 million years. Back then, before life on land existed, brachiopods were one of the most common animals on our planet. They lived at the bottom of the sea and used their muscular foot to cling on to the rocks. There were so many that they sometimes formed reefs. Brachiopods are one of the most common fossils you can find in Northumberland, because we have a lot of Carboniferous limestone. You can find it in the rocks on the coast at Howick, or Scremerston and in disused old limestone quarries inland. Sometimes you see the whole shells, sometimes just curved white lines in the rock – where the shell has been mostly eroded away and you are looking at a cross-section.

Gigantoproductus isn’t alive today but brachiopods are. They are uncommon in the seas around Britain and live in cold water regions nearer the poles. While there have been more than 30,000 species of brachiopods in Earth’s history there are probably less than 400 species alive today.

Vote for the County Rock and Fossil for Northumberland

Each person may vote for one rock and one fossil.