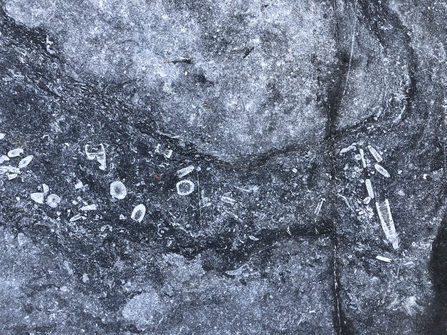

Fossils of 330 million year old 'sea lilies', aka crinoids, a relative of the modern sea urchin, petrified in limestone on a Northumberland foreshore. Image by: Ian Jackson.

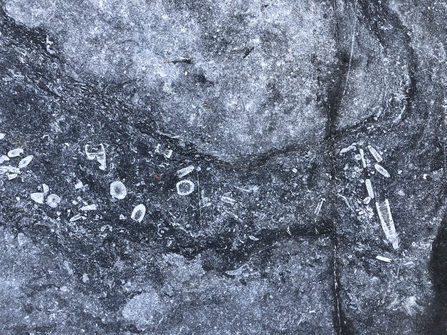

Fossils of 330 million year old 'sea lilies', aka crinoids, a relative of the modern sea urchin, petrified in limestone on a Northumberland foreshore. Image by: Ian Jackson.

This is why geologists spend time during their degrees looking over the faculty fences at geographers and biologists. Modern Earth systems and the anatomy and lives of contemporary plants and animals help them understand what went before.

These cross-overs and connections between the living and the fossilised happen all over the place. I already touched on one in a previous blog; the mires and bogs we are blessed with in Northumberland. They start off as meres in glacial scrapes, become colonised by sphagnum, bog asphodel, cranberry and sundew and within a relatively short time (to a geologist at least) become peat. Something to be dated by Carbon14 and provide invaluable evidence of the way our climate and environment has changed over time. But there are more links.

When you are next up at Hauxley, take a walk along the beach. Look at the little ‘cliff’ and the foreshore which are being eroded by rising tides. Sandwiched between the dune sand at the top and the stony glacial clay at the bottom are layers of sand and peat, often with tree trunks sticking out. The story is complex, but put simply, these tell of a time 8,000 years ago when you could walk from Amble to Antwerp and keep your feet dry. A time when our ancestors hunted red deer in forests which are now drowned. This is a tale that needs biologists, geologists and archaeologists working together to unravel it.

At the detailed level there are many factors which will influence the distribution of our plants and thus animals. Climate, slope, micro-aspect and the interaction between organisms all come into play. But at a broad level, across this county and the world, geology - the rocks, landforms and soils it produces, is a fundamental controlling variable and determines our basic biodiversity.

At Harbottle Crags the thin acidic soils over the Carboniferous Fell Sandstone support ubiquitous heather. NWT’s newest reserve, Benshaw Moor, has a mosaic of acid and alkali habitats developed over a varied sandstone and limestone geology. Along its sinuous outcrop from Bamburgh to Walltown, the Whin Sill dolerite produces thin soils tolerated by grasslands which can deal with its deficiencies.

I came across a wonderful geology and wildlife link recently. Most people have heard of how we use chemical isotopes to identify where our ancestors came from. It works like this: when they were alive the things our forebears ate and drank left microscopic deposits from local rocks in their teeth and bones. That chemical ‘signature’ tells us where they came from. Well it seems that US scientists are now using the same isotopic technique in birds’ feathers to track down the migration paths of elusive raptor juveniles. Who needs GPS tracking devices when you’ve got rocks?!

Let’s head back nearer home, to the coast and go look on the strand line for empty shells. Often thousands of just one or two species, like cockles and whelks, collected and concentrated by the tide. Then go search the rocks. In limestone layers, for example just south of Cullernose Point and at Sugar Sands Bay you will find fossilised fragments of a 320-million-year old seashell called Gigantoproductus and little cylindrical beads - crinoids - an ancient relative of the sea urchin called a sea lily. Why are these fossils all together in these rocks? Just like those modern shells on the strand line, once they had died, the tidal actions of a long gone sub-tropical sea collected their shelly remains all together. Uniformitarianism.

So we rock folk have a lot of time for biologists and ecologists (and even occasionally, provided they don’t stray too far from the surface, for geographers and archaeologists); it would be nice to think the feelings are mutual. We’d like the climatologists to cosy up to us a bit more too. Predicting our future climate when we are exceeding historic norms isn’t easy and if the present is the key to the past, then isn’t it reasonable to believe that the past is the key to the future?